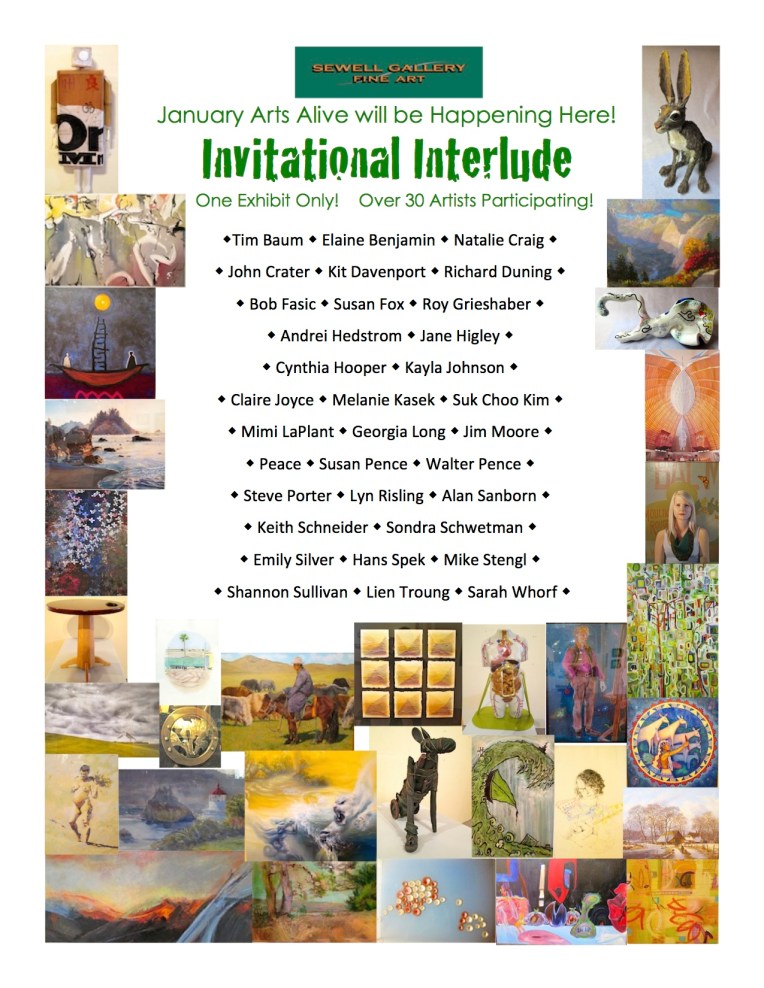

I’m proud to announce that I will be one of the participating artists in the Sewell Gallery’s first “Invitational Interlude”. The opening reception will be during January Arts Alive in Eureka, California on January 5 from 6-9pm. The gallery is located at 423 F St. You can call 707- 269- 0617 for more information. You can read more about this very special art event here.

Mongolia

Mongolia Monday- Mongol Artist Tod Otgonbayar

I got an email recently from a Mongol artist asking me to introduce his website. I checked it out and found that I was more than happy to do so. And that’s not all. It seems that I had already “met” Mr. Otgonbayar through the art he created for Mongol postage stamps, which I blogged about in January of 2011. Small world.

He left Mongolia in 2004. The country was still in transition from communism and his politically inspired art was a problem, so he went to Russia and then on to England, which is where he and his family now live.

He paints as he pleases now, in a number of styles and themes, including surrealism, dada, tantra and maybe my favorite, tachism. His work is highly colorful and full of symbolism. There is a good selection on his website, including more of the postage stamps that he created. I encourage you to take a look!

Mongolia Monday- Explorers and Travelers: Excerpt From A Great Book About Mongolia, “Mongol Journeys” And A Reminder

Don’t forget to check out my 2013 calendar filled with images of my paintings of Mongolia! It includes “Done for the Day”, which was accepted into the Society of Animal Artists prestigious juried show “Art and the Animal” in 2009.

—————-

Owen Lattimore was, in his time, considered one of the greatest western experts on Mongolia. He traveled extensively in what were then called Inner and Outer Mongolia in the 1930s. The former is now an autonomous region of China and the latter is the independent country of Mongolia. He revisited Mongolia in the early 1960s. I just finished his book “Mongol Journeys” and would have to say that it is one of the best books on Mongolia that I have read yet. It’s not easy to find, but you can currently get it here for a reasonable price.

I’d like to quote from it today about the traditional Mongol view of names for things. It’s a pretty good example of how untrue and simplistic the overgeneralizing statement is that “people are all alike”. In fact, people in different parts of the world operate from very different cultural assumptions which can, in equal parts, trip up, amuse or, with luck, enlighten a visitor and give them an insight into a different way of seeing the world.

For example, the exploration of America often consisted in being first to a place and then giving your name to it. If the name stuck, then it was the one that appeared on all maps henceforth down to today. We even get a kick out of places that have had the same place name for a very long time. For many Americans (I can speak only to my country, others may be the same though), the first thing they ask when arriving at a sight like a mountain or river or waterfall is to ask what it’s called.

But for the Mongols:

“Another very interesting thing about nomad life is the balance between the specific and the vague. In the Mongol vocabulary, for instance, the age, colour and individual characteristics of a horse or a camel or any other animal can be told with the most minute precision. There is also such an accurate terminology for different kinds of hills, ridges, plains, lakes, pools, streams and springs that you can get directions taking you across many miles of vague country without a mistake. On the other hand, it is often difficult to get a precise place name. A hill or a spring may have several names, of which some are descriptive and others honorific or propitiatory. The “real” name is likely to be taboo, so that if you ever hear it at all you are more likely to hear it when you are far away than when you are near it.

Why such taboos? Well, to begin with, if you are at a certain place you are obviously in some ways dependent on that place – for a safe camp, for good pasture and so on. It is better, therefore, to talk about that place vaguely in a ‘respectful’ way than exactly in a ‘familiar’ way. Even more important, perhaps, is that fact that, being a nomad, you do not want to be tied to any one place even by verbal associations. It is true that neither the Mongols nor any nomads are unlimited wanderers; you move in a framework which is partly the social frame of your tribe and partly the geographical frame of your tribe’s territory….the fact that you are a herder means that you always long for fluidity of movement. The Mongols, as nomads, call themselves nutel ulus, moving people….Your “homeland” is your nutuk (today this is spelled “nutag”)…your nutag is not only ‘the territory within which you move’ but ‘territory in which you are always moving about’.

Within this territory you do not want to be pinned down to any one place, nor do you want to be easily traced or spotted by an enemy (Note from Susan: this was written in the 1930s when there was still intertribal conflict and banditry in both Inner and Outer Mongolia). At the same time you do want your friends to be able to find you and you must be traceable by the authorities…..All of this explains why, when you are travelling and either asking your way or being asked from where you have come and where you are going, there are two extreme answers and any number of gradations in between; the vague answer and the exact answer. It all depends on the authority of the questioner and the degree to which the man questioned recognizes that authority and the necessity of being indentified or the desire to be traced. When, in short, you sometimes find yourself thinking that the nomad is frank and honest and at other times that he is evasive and a liar you must remember that this is as much a social convention as it is of personal veracity.”

My own personal experience with this whole cultural issue of place names was on my 2009 trip to Mongolia, heading south to Baga Gazriin Chuluu Nature Reserve. We stopped for lunch on a hillside with a view to an amazing mountain that rose out of the steppe. Naturally I asked what it was called. My guide/driver said “Hairhan”, which means “sacred”. Then he explained how the Mongols do not, out of respect, say the name of a mountain while in its presence. They are all called “Hairhan”. I observed that it got around the question like the one I had asked, that a visitor could ask the name, get an answer and be content, while the Mongol had preserved the correct cultural practice. And, in fact, I follow it myself now. If someone asks me the name of a mountain (they are all sacred since the top of a mountain is the closest one can get to Tenger, the Eternal Blue Sky), I say “Hairhan”, but also explain what that means and that I will tell them the “real name” once we are out of the mountain’s presence. It just feels like the right thing to do.

Mongolia Monday- Gift Idea: My 2013 Calendar Is Now Available!

You can now enjoy images from the Land of Blue Skies every month of the year through the paintings in my 2013 calendar. Mongol horses, takhi, argali, herders, yaks and camels, they’re all here.

Visit my shop on Zazzle and order one today! You will also find tote bags, coffee mugs and real US postage stamps with my Mongolia images on them.

Also, don’t forget to check out the page with my small original oil paintings.

New Painting Debut! “Mongol Horse #9- Friends”

I’ve been having fun painting Mongol horses. This and the previous one, which you can see here, were started before my latest trip to Mongolia.

The reference photo was shot at the beginning of my 2011 trip with fellow artist Pokey Park. We had spent a few days in Hustai National Park photographing and observing takhi. Now we were on our way south. We had left the park and were driving to the only bridge for many miles that crosses the Tuul Gol, traveling along an upland area that overlooked the river valley.

The rocks on the right are part of a complex of Turkic graves, which are quite interesting. But not nearly as interesting to me as the herd of horses that were behind me when I took the above photo.

The rocks on the right are part of a complex of Turkic graves, which are quite interesting. But not nearly as interesting to me as the herd of horses that were behind me when I took the above photo.

It was August and there were a lot of flies. The horses were constantly circling, trying to get their heads as far into the middle of the group as possible. But they knew I was there and every once and awhile some would stop and look at me, which is when I got the reference photo I used for the painting.

It was August and there were a lot of flies. The horses were constantly circling, trying to get their heads as far into the middle of the group as possible. But they knew I was there and every once and awhile some would stop and look at me, which is when I got the reference photo I used for the painting.

I liked the contrast of color and head position of these two, so I cut out everyone else. The twisted blue khadag around the neck of the brown horse was a nice extra.

I liked the contrast of color and head position of these two, so I cut out everyone else. The twisted blue khadag around the neck of the brown horse was a nice extra.

Mongolia Monday- Music, Part 3: Something Old, Something New

For the final part of this three-part series, here are three videos that, to me, show one of the most interesting and fun parts of contemporary Mongol music, the synthesis of traditional and modern forms.

Altan Urag is probably the best known group outside of Mongolia, due to their attendance at many internatinal music festivals. They play what we would call “Neo-folk” music, traditional songs uniquely interpreted. This one, “Khiliin Chadad” combines traditional Mongol instruments like the morin khuur (horse head fiddle), Jew’s harp (used by Mongol shaman), plus khoomii (throat-singing) with a Middle Eastern-sounding drum rhythmn and Spanish-style guitar. It’s quite a combination.

Hurd, whose lead singer is Chono (“wolf” in Mongolian), is one of the most famous rock bands in Mongolia. The song, Eh Oron ( which I think should have been spelled Ikh Oron), is a rock anthem, with morin khuur. The video’s visuals are a photographic journey through both the land and traditional culture of the country. Picture Led Zepplin extolling the virtues of the English countryside and the various activities at county fairs with a violin section added in the middle. But somehow, in Mongolia, it all makes perfect sense.

Javhlan, one of Mongolia’s most loved singers, has a world-class voice and then some. He only records traditional songs. But he sets them to a variety of western rhythms…samba, waltz, pop and others. He often wears traditional Mongol men’s clothing in his videos, as in this one, and usually includes lovely shots of the land. I’ve been told that these days he lives out in the countryside in a ger and I’ll bet it’s a really nice one. I have six or seven of his CDs loaded into iTunes and listen to him often while I’m painting.

I Get International And Local Media Coverage!

In one of those little incidents of sychronicity that come along every once in awhile, I’ve just had three articles about me, my art and Mongolia appear in three publications in less than a week.

It started with a Facebook message on November 3 from a editor for The Epoch Times, a Chinese-American news website and print publication which is published in 35 countries and 18 languages and is dedicated to providing uncensored news to the Chinese people. The editor, Christine Lin, found me through my Facebook public page after she had a problem using the contact form on my website (which is now working fine as far as I know). One lesson from this is that it pays to have multiple ways for people to contact you if you are an artist. We did a one hour phone interview which resulted in a 1500 word article that included six images of my art. You can read “American Artist Susan Fox Paints Genghis Khan’s Mongola” here.

The next contact came through LInkedIn. I was looking through the list of possible contacts the site provides based on who your current connections are. One of them was Allyson Seaborn, who writes for the UB Post, the leading English-language newspaper in Mongolia. What caught my eye at first, though, was that some of her page was in Mongolian cyrillic. I sent her a connect invitation, she accepted and then a day or so later sent me a message asking if I’d be willing to be the subject of one of her regular expat (expatriate) columns. I told her that I don’t live in Mongolia, but she felt that I have traveled there extensively enough (7 trips so far) and that being an artist would be interesting to their readers. In this case, she sent me a short list of questions about me, my work and my activities in Mongolia. There was also a list of set questions that every subject of the series answers. You can read “Susan Fox- There is no other place like the Land of Blue Skies” here.

The third article, for our local newspaper the Times-Standard, had been on my To Do list since I had come home from Mongolia in late September. In this case it was something I wrote myself, which was mildly edited, and submitted with a zip file of images, but I had no idea that it would appear yesterday. You can read “Local painter takes art expedition to Mongolia” here.

Mongolia Monday- Music, Part 1: Three Traditional Forms

I thought I’d do a three part series on Mongolian music, using YouTube videos that I’ve found, and starting with three traditional forms- khoomii (throat singing), Urtyn Duu (long song) and morin khuur (horsehead fiddle). Next week, it will be Mongolian musicians and singers performing in western musical genres like rock and the third week will be music that is a synthesis of the first two.

You can read more about Mongolian music here.

Khoomii may the musical form best known by westerners due to a number of “folk” CDs available that feature throat singing, which originated in western Mongolia in an area just to the south of the Khar Us Nur lake complex.

Urtyn Duu means “long song”, but not that the songs themselves are long. The name refers to the singer stretching out the syllables of the words. Although both genders sing this form, the most famous long singers seem to be women.

Morin Khuur is the horsehead fiddle, probably the most famous Mongolian musical instrument and is one of the symbols of the country. With only two strings, the player can create truly beautiful musical sounds and also perfect imitations of the sounds that horses make. The selection in the video is one of my most favorite pieces of Mongolian music, “Mongolian Melody” by one of Mongol’s most esteemed composers, Jantsannarov.

Learning What Siberian Ibex Look Like

What? You say. She’s seen them and photographed them. Surely she knows what they look like. Well, in a manner of speaking, I do, of course. I’ve got quite of bit of reference of them from previous sightings and have done a couple of small paintngs. But until this past trip I didn’t really have sharp, close-up reference of ibex in good light and also doing interesting things. Now I do.

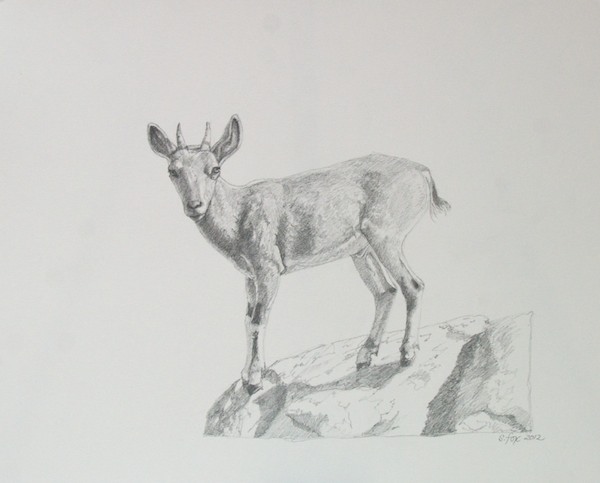

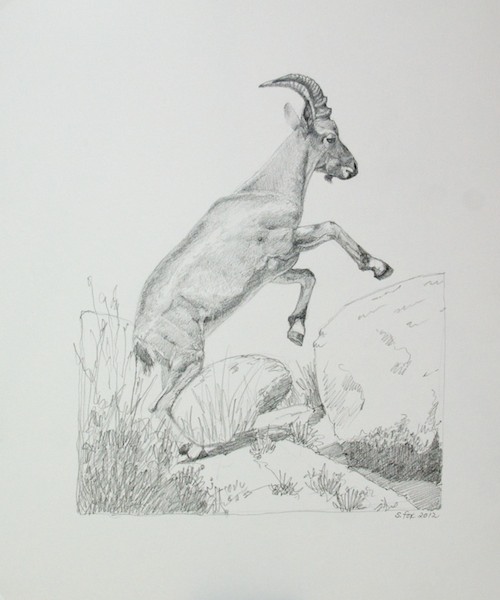

I spent three out of my first four mornings at Ikh Nartiin Chuluu Nature Reserve in August taking around 1000 photos of 2-3 groups of nannies, kids and young billies. I’ve done an initial sorting and 5-star rated (in Aperture, my image management software) the ones that caught my eye for possible paintings.

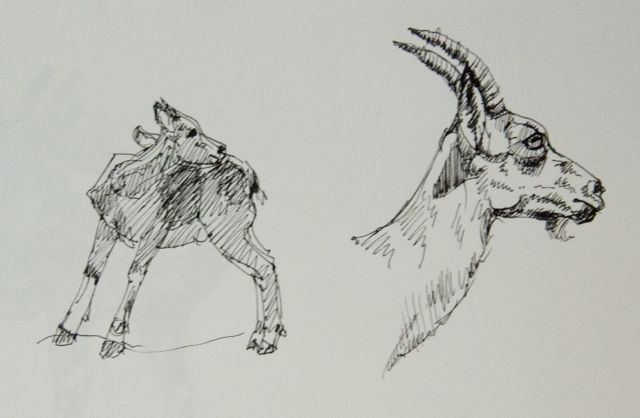

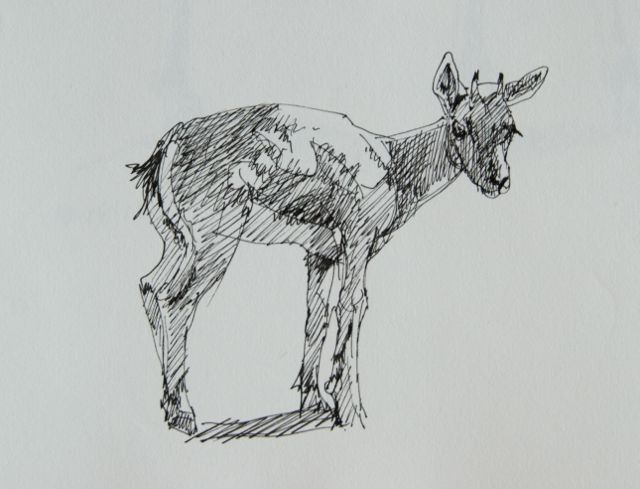

But…I’ve learned when I decide to paint a new species that I’ll be sorry if I just dive in and hit the easel. I first need to “learn what the animal looks like” and to do that I simplify things by doing a number of monochrome sketches and drawings to familiarize myself with their structure, proportions and anatomy, along with looking for interesting behaviors. I pick reference photos that have a strong light and shadow pattern or some kind of interesting, perhaps, challenging, pose. Sometimes I throw in a quick indication of the ground so I can start to think about that, too.

I like doing small, fairly quick pen sketches. For those I use Sakura Micron .01. and .02 pens on whatever sketchbook I have on hand. They give me a basic idea of what I need to know. Then I’ll often do some finished larger graphite drawings on vellum bristol. I also did a couple of iPad drawings using ArtRage, which makes it easy to lay in some color.