Contest result: No one got all the noses right. The right answers are: grizzly, bison, moose, turkey vulture, elk. The person who came the closest guessed black bear instead of grizzly because the muzzle wasn’t dished, but nailed all the rest. This may be because it was a young animal. I went back to my reference and took a good look at my pictures of black bear and I think, in fairness, that I didn’t do a good enough job making it clear in my drawing which was which, so I would like to announce that Heather Houlahan is the winner and will be getting a packet of my notecards. Congratulations and thanks to everyone who entered!

On to mouths. After eyes, the mouth may be the most defining part of an animal’s head. These drawings were done with a Venetian Red Derwent Drawing Pencil. They’re kind of waxy, like Conte crayon as opposed to chalkier, for lack of a better term, like hard pastels. The paper is, once again, vellum bristol.

All of today’s examples are from Kenya.

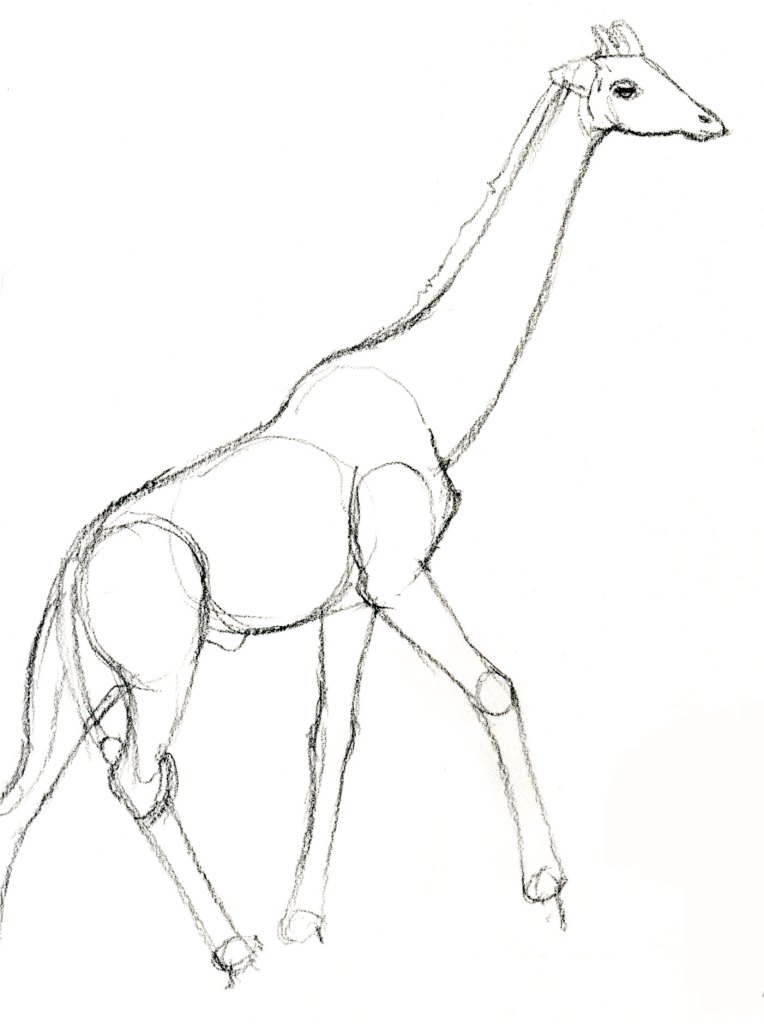

First up, a reticulated giraffe that I photographed in the Samburu, Kenya in 2004.

Giraffe lips, believe it or not, are very interesting. As anyone who has fed a giraffe at a wild animal park knows, the upper lip is extremely flexible, almost prehensile. What is really impressive, however, is that the mouth is so tough that a giraffe can wrap it’s tongue around a very thorny acacia branch, pull it loose, stick it in its mouth and chew it without a second thought or, apparently, getting punctured.

_

This is the mouth of a white rhino that I photographed at the Lewa Downs Conservancy, south of the Samburu, also in 2004. Lewa is one of the best places to see these prehistoric-looking beasts. White rhinos, when seen from the front have a square lip. Black rhinos’ lips come to a point. According to Wikipedia, there is no actual evidence that the word “white” is a mis-translation of the Afrikaaner word for “wide”.

This is the mouth and muzzle of a Coke’s hartebeest, a large antelope, which I saw in the Masai Mara, Kenya. It has a very long head. When I enlarged the image to see the mouth better, I was struck by how its shape and the shape of the nose flowed together in an almost art nouveau manner. Just the kind of thing I look for.

This is the mouth and muzzle of a Coke’s hartebeest, a large antelope, which I saw in the Masai Mara, Kenya. It has a very long head. When I enlarged the image to see the mouth better, I was struck by how its shape and the shape of the nose flowed together in an almost art nouveau manner. Just the kind of thing I look for.

Also from the Mara, this is the mouth of a spotted hyena. Their jaws are trememdously strong and can break large bones apart. And, as you can see, are filled with teeth. Studies have proved that they hunt at least as much as they scavenge. They live in female-centric “clans” in a defined territory that they defend against anything, even lions. I really enjoyed watching them and hearing them “whoop” at night.

Also from the Mara, this is the mouth of a spotted hyena. Their jaws are trememdously strong and can break large bones apart. And, as you can see, are filled with teeth. Studies have proved that they hunt at least as much as they scavenge. They live in female-centric “clans” in a defined territory that they defend against anything, even lions. I really enjoyed watching them and hearing them “whoop” at night.

This is the muzzle of a young lion I saw in the Mara. No scars yet and it has an almost soft quality that will change as he gets older.

This is the muzzle of a young lion I saw in the Mara. No scars yet and it has an almost soft quality that will change as he gets older.

Finally, I was out in the safari vehicle at dawn, also in the Mara, when we came upon a lioness who was just waking up. She gave us a REALLY big yawn, got up, stretched and ambled off. Keeping everything lined up and in decent perspective was challenging as you can see from the erasure marks.

Next week the eyes have it and then I’ll put it all together.

Using the image on the monitor, I did this value study-

Using the image on the monitor, I did this value study-

The finished study. The shadow area is treated as one big shape and I’ve “lost” all the rest.

The finished study. The shadow area is treated as one big shape and I’ve “lost” all the rest. The starting image; a white rhino I photographed at the Lewa Downs Coservancy, Kenya, in 2004. The light side and shadow side are very distinct.

The starting image; a white rhino I photographed at the Lewa Downs Coservancy, Kenya, in 2004. The light side and shadow side are very distinct. The initial drawing. Why red? I could make up a really cool explanation, but actually I picked it up from Scott Christensen. Sometimes I use other colors depending on what I have in mind for the painting, but I tend to fall back on the red for these quick studies. One less decision to make.

The initial drawing. Why red? I could make up a really cool explanation, but actually I picked it up from Scott Christensen. Sometimes I use other colors depending on what I have in mind for the painting, but I tend to fall back on the red for these quick studies. One less decision to make. Once again, I’m laying in the shadow as one big shape.

Once again, I’m laying in the shadow as one big shape. I’ve added color to the light side and also used the same tone for the background. Notice that I have left brush strokes showing for visual texture and that there are four different color temperatures in the shadow.

I’ve added color to the light side and also used the same tone for the background. Notice that I have left brush strokes showing for visual texture and that there are four different color temperatures in the shadow. I’ve now covered the background with paint and picked out the lightest areas on the rhino.

I’ve now covered the background with paint and picked out the lightest areas on the rhino. The finished study, which took less than two hours. I lightened the background to pop out the shadows, added a darker tone on the left to pop out the side of the head and added some final brushstrokes at the bottom to suggest grass.

The finished study, which took less than two hours. I lightened the background to pop out the shadows, added a darker tone on the left to pop out the side of the head and added some final brushstrokes at the bottom to suggest grass.

For a Bactrian camel head study, I looked for reference with a 3/4 view, but most of what I have didn’t seem like it would draw well because the position of the features is so odd. Time was limited, so I stayed with a classic profile that shows his calm, unexcitable nature. My husband and I got to sit with a large group of camels at Arburd Sands when we were in Mongolia and I could practically feel my blood pressure drop as I sat and sketched them.

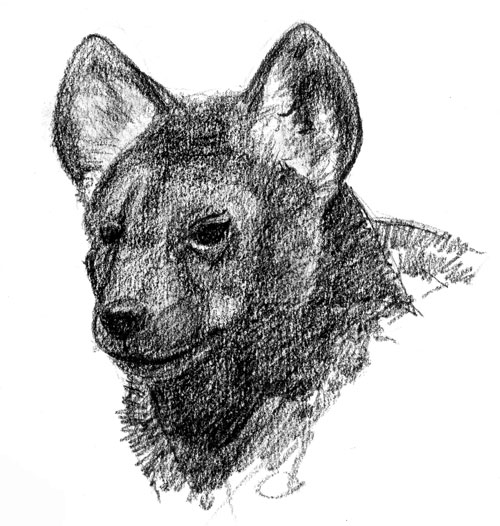

For a Bactrian camel head study, I looked for reference with a 3/4 view, but most of what I have didn’t seem like it would draw well because the position of the features is so odd. Time was limited, so I stayed with a classic profile that shows his calm, unexcitable nature. My husband and I got to sit with a large group of camels at Arburd Sands when we were in Mongolia and I could practically feel my blood pressure drop as I sat and sketched them. The body of this spotted hyena got too big, so I cropped her at the shoulders, which gives a different look than the camel above, in which the drawing trails off in value, number of lines and amount of detail. I find hyenas interesting and compelling on a number of levels. They live in a matriarchal clan structure, will go to war with lions and move a lot faster than you think they can with their gallumping, awkward gait. The African night wouldn’t be the same without their crazy whooping and insane giggling.

The body of this spotted hyena got too big, so I cropped her at the shoulders, which gives a different look than the camel above, in which the drawing trails off in value, number of lines and amount of detail. I find hyenas interesting and compelling on a number of levels. They live in a matriarchal clan structure, will go to war with lions and move a lot faster than you think they can with their gallumping, awkward gait. The African night wouldn’t be the same without their crazy whooping and insane giggling. I love the flow of the pose I captured at Yellowstone as this coyote ran parallel to the road in nice morning light. The head demonstrates that you can get a lot of character without a lot of detail if you make your marks carefully, see the shapes correctly and don’t get hung up in drawing individual hairs.

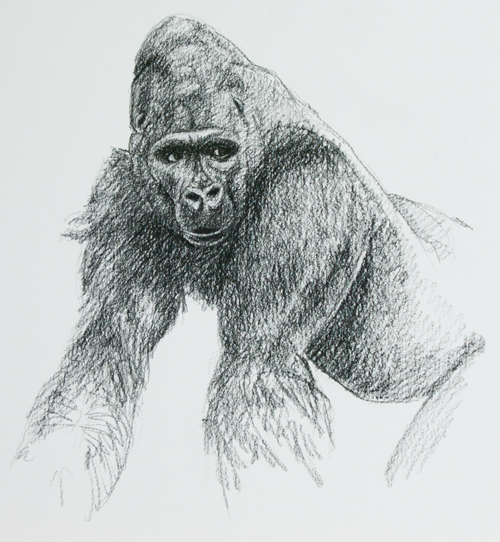

I love the flow of the pose I captured at Yellowstone as this coyote ran parallel to the road in nice morning light. The head demonstrates that you can get a lot of character without a lot of detail if you make your marks carefully, see the shapes correctly and don’t get hung up in drawing individual hairs. This drawing and the next one ended up too big to scan, so they were photographed and then processed in Photoshop. They were done on white paper, but I kind of like the toned effect. In any case, I’ve rarely done primates, but I got some incredible reference of the gorillas the last time I was at the San Francisco zoo and have been looking forward to seeing what I could do with it. The big silverback male was on morning patrol and he didn’t miss a thing.

This drawing and the next one ended up too big to scan, so they were photographed and then processed in Photoshop. They were done on white paper, but I kind of like the toned effect. In any case, I’ve rarely done primates, but I got some incredible reference of the gorillas the last time I was at the San Francisco zoo and have been looking forward to seeing what I could do with it. The big silverback male was on morning patrol and he didn’t miss a thing. Sometimes a subject serves itself up on a silver platter and is so compelling that the artist’s job is to simply not mess it up. I found warthogs to be, pound for pound, THE most entertaining animal I saw in Kenya. This one was at Lewa Downs, grazing near the lodge we stayed at. He’s got it all: great ears, that remarkable face and the solid body carried by relatively delicate-looking legs and feet.

Sometimes a subject serves itself up on a silver platter and is so compelling that the artist’s job is to simply not mess it up. I found warthogs to be, pound for pound, THE most entertaining animal I saw in Kenya. This one was at Lewa Downs, grazing near the lodge we stayed at. He’s got it all: great ears, that remarkable face and the solid body carried by relatively delicate-looking legs and feet.

A Holsteiner stallion, who I did a portrait commission of year before last.

A Holsteiner stallion, who I did a portrait commission of year before last. A bighorn sheep ewe from the Denver Zoo.

A bighorn sheep ewe from the Denver Zoo. A serval, also from the Denver Zoo.

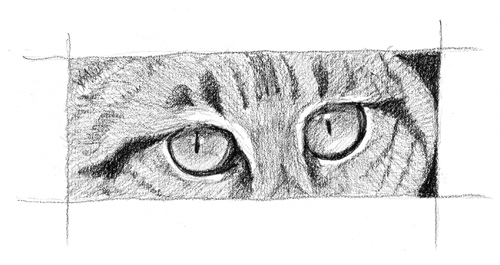

A serval, also from the Denver Zoo. And our own dear tabby girl, Persephone, aka The Princess.

And our own dear tabby girl, Persephone, aka The Princess.

This is the mouth and muzzle of a Coke’s hartebeest, a large antelope, which I saw in the Masai Mara, Kenya. It has a very long head. When I enlarged the image to see the mouth better, I was struck by how its shape and the shape of the nose flowed together in an almost art nouveau manner. Just the kind of thing I look for.

This is the mouth and muzzle of a Coke’s hartebeest, a large antelope, which I saw in the Masai Mara, Kenya. It has a very long head. When I enlarged the image to see the mouth better, I was struck by how its shape and the shape of the nose flowed together in an almost art nouveau manner. Just the kind of thing I look for. Also from the Mara, this is the mouth of a spotted hyena. Their jaws are trememdously strong and can break large bones apart. And, as you can see, are filled with teeth. Studies have proved that they hunt at least as much as they scavenge. They live in female-centric “clans” in a defined territory that they defend against anything, even lions. I really enjoyed watching them and hearing them “whoop” at night.

Also from the Mara, this is the mouth of a spotted hyena. Their jaws are trememdously strong and can break large bones apart. And, as you can see, are filled with teeth. Studies have proved that they hunt at least as much as they scavenge. They live in female-centric “clans” in a defined territory that they defend against anything, even lions. I really enjoyed watching them and hearing them “whoop” at night. This is the muzzle of a young lion I saw in the Mara. No scars yet and it has an almost soft quality that will change as he gets older.

This is the muzzle of a young lion I saw in the Mara. No scars yet and it has an almost soft quality that will change as he gets older.

I’ve personally found the 3/4 view difficult, at least partly because I know that the camera flattens and distorts the form. This is a case where I draw what I know rather than what I see in the image.

I’ve personally found the 3/4 view difficult, at least partly because I know that the camera flattens and distorts the form. This is a case where I draw what I know rather than what I see in the image.

Profile is good, also. Then you can see how the nose fits into the rest of the head without worrying about perspective. Pick what you want to emphasize and downplay the rest.

Profile is good, also. Then you can see how the nose fits into the rest of the head without worrying about perspective. Pick what you want to emphasize and downplay the rest. Bird’s beaks are really hard to see close up in the field, generally because they’re small and the owners don’t tend to hold still for long. A captive bird may be your best bet because you don’t want to get caught faking it. But beware captive raptors whose beak tips won’t show the wear that the wild ones will.

Bird’s beaks are really hard to see close up in the field, generally because they’re small and the owners don’t tend to hold still for long. A captive bird may be your best bet because you don’t want to get caught faking it. But beware captive raptors whose beak tips won’t show the wear that the wild ones will. Cat noses are fairly similar in form. Variations on a theme, more or less. So drawing your house cat’s nose can be good practice for the big, wild guys.

Cat noses are fairly similar in form. Variations on a theme, more or less. So drawing your house cat’s nose can be good practice for the big, wild guys. It’s always great to get good reference of unusual angles, like this one looking up. It helps to see how the lower jaw fits with the upper jaw. Note how I have created a sense of three dimensional form by “wrapping” the right hand upper lip around the lower jaw.

It’s always great to get good reference of unusual angles, like this one looking up. It helps to see how the lower jaw fits with the upper jaw. Note how I have created a sense of three dimensional form by “wrapping” the right hand upper lip around the lower jaw.

The only real difference is the position of the head, but the 3/4 view really changes the flow of the top line and actually stops the sense of movement.

The only real difference is the position of the head, but the 3/4 view really changes the flow of the top line and actually stops the sense of movement.