Last week was pretty intense. I had a painting to finish for submission to an invitational show (which it may or may not be accepted into; we’ll see). It’s by far the most complex and difficult one I’ve taken on so far. The kind where, once you’re well into it and can see what level of effort it’s going to take to pull it off, you wonder if you’re out of your mind. But I felt really driven to paint it, so off I went. I think it took somewhere between 60 and 80 hours, spread over about three weeks, but I wasn’t really counting. I didn’t have time.

I normally post about my painting activities on Fridays, but when you see the reference image that inspired me, I think you’ll agree that it’s right for Mongolia Monday.

I photograph the process when I do “major” paintings, both to have a record and to be able to refer back to previous points while it’s in progress. I thought you might enjoy following how this one developed.

So, to start, here’s the image that said “PAINT ME!” It was taken at a local Nadaam in the town of Erdene, which is about an hour east of Ulaanbaatar, in July of 2009. It was pouring rain when we arrived, just in time to see the finish of the horse race. Fortunately, it stopped and, although it was cloudy and muddy, we had a great time and I got at least three or four more painting ideas from the afternoon.

I loved everything about this image: The two horses neck and neck. The fact that one boy is using a traditional Mongol wood saddle and the other is riding bareback in stocking feet and how different it makes their body positions as they ride flat out for the finish line. The way the orange and yellow is repeated in their clothes and the saddle.

The only thing missing was great light. Hum, what to do? I decided that rather than trying to change the light, since July is the rainy season (or at least it’s supposed to be) in Mongolia, which means that at least some of these races happen in wet conditions, I’d just go with it and make the fact that it was a rainy day part of the story.

The background didn’t do anything for me and since most of the people who will view the final painting won’t be familiar with the setting or situation, I needed to add some context. The first step was to do a pencil drawing that included all the elements to make sure everything would go together even though I used at least six different photos for the final composition.

The drawing is done on 19×24″ tracing paper. The finished painting is 28×36″. The grid lines are a traditional (dated back to the Renaissance) method of transferring a drawing to the larger surface. Notice how many spectators there are and where the buildings are. I had already decided to leave out a line of cars that were behind the people.

I have also decided to paint these scenes as I see them. I’m not going to “romanticize” them by substituting traditional hats for the baseball caps or putting the kids in del. While I’m very interested in Mongolian history and might do paintings with historical themes, with historic costumes and armor, if I can get the reference, for the most part I’m interested in Mongolia as it really is right now, in the 21st century.

Once the drawing is transferred to the canvas with a pencil, I re-draw it with a brush, always correcting and refining as I go.

In this case, I decided to start by laying in the background first. I wanted to establish the lightest lights and also the atmospheric perspective of the mountains in the distance. You will also notice that I’ve ditched all the people on the right and cut down the number of people on the left. The buildings are gone, too. I really felt that I needed to simplify things. One of the lessons I’m learning is how what works at one size may not work at a much larger size. It’s what stalled me on the big argali painting.

Next, I laid in the first layer of color on the figures, going dark so I could come back in with lighter colors. Everything is in what is called “local color”-the “real” color of an object not affected by a light source. Notice the drawing is pretty much gone, but that’s ok because, I know I can get it back as I go.

Now, I’m past the opening stages. The set-up is done and the constant process of painting, correcting and refining has begun. I’ve laid in the folds on the boy’s clothes and gotten the basic modeling done of the muscles and structure of the horses. Where before, the background had seemed too crowded, now it seems too empty and the people are just standing there, isolated, with no context.

Here you can see how I work. The computer is a 24″ iMac with a glossy monitor, so it’s like painting from very large transparencies. I can easily toggle back and forth between the various images that I’m using. You can see that I’ve added the buildings back in, but now they are behind the spectators, which creates one visual unit instead of two scattered ones. And now there are gers in the background. I’m thinking at this point about the white of the boy’s hats being repeated in the hats of two of the spectators, then repeated again with the gers. So it’s kind of like a bar of music with the white elements as the “notes”.

Here’s a detail of the people and buildings in progress. The good people of Erdene would probably be really confused if they saw this because I’ve used my “artistic license” to move and rearrange the structures to suit me. But I’d like to think that they’d recognize their friends and neighbors. Unfortunately, the pattern on the one woman’s blue del ended up being too visually distracting, so I had to make it just a plain blue. All the colors are intended to relate to each other in a somewhat limited palette and not compete with the jockeys. Oh, and that’s the Mongolian flag at the top of the blue building. Couldn’t leave that out. Notice also that I’ve added the road that runs through the town. It’s on a diagonal, which is more dynamic than a horizontal. I want it to support and emphasize the main action. That’s also why the lines of dirt at the horses feet are on the diagonal, as you can see in the image above.

Here’s a detail of the jockey’s faces in progress, along with the horse’s heads. They all went through three or four repaints before I got them the way I wanted them. Notice that I haven’t painted any of the tack yet, other than the orange saddle. That’s the final level of detail that I leave for the final orchestration. Also, the paint has to be dry so that if I make a mistake on a stroke I can pull it off without wrecking what I’ve done underneath.

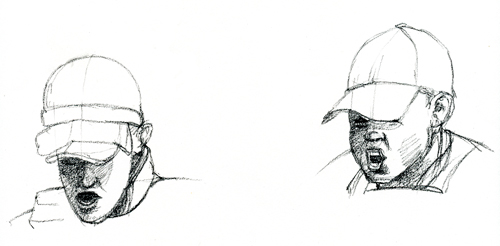

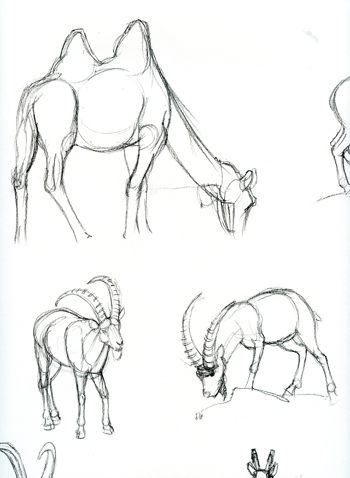

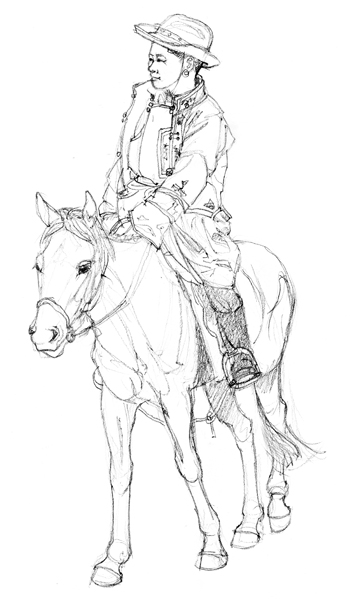

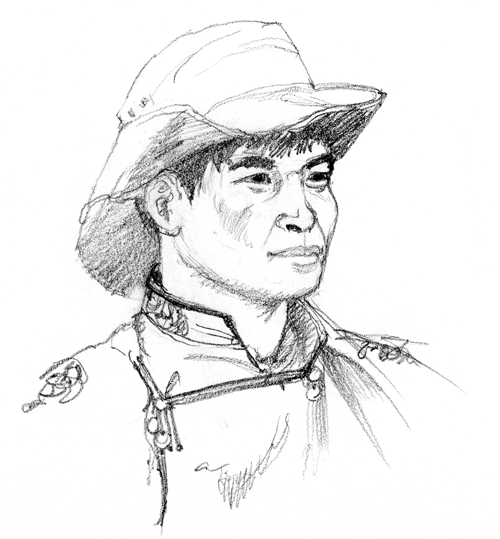

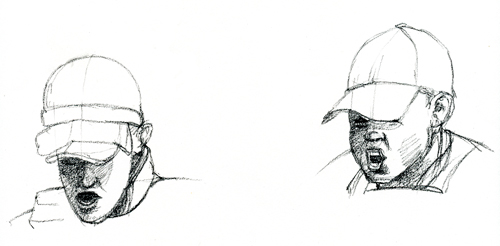

At one point, I stopped, got a piece of paper and a charcoal pencil and did a couple of studies of the boys and the bridle of the horse on the right to make sure that I understood the shapes correctly and could paint only the ones I needed.

I highly recommend this. Instead of flailing around in paint, hoping to somehow get it right, do a quick drawing to work out the problem. It saves a lot of time, paint and frustration.

One thing I noticed almost at the end was that, as a design decision, I had the right-hand horse’s tail flowing off the canvas. When I was looking at another image for another reason, it hit me and I remembered that the race horse’s tails are bound part-way down. What an awful mistake that would have been. Quick scrap down and repaint.

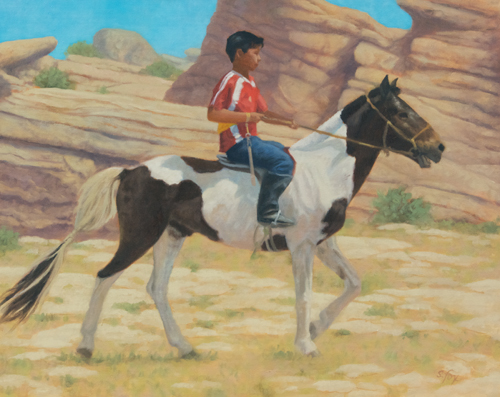

And here is the finished painting: Rainy Day Finish; Erdene Nadaam, 2009