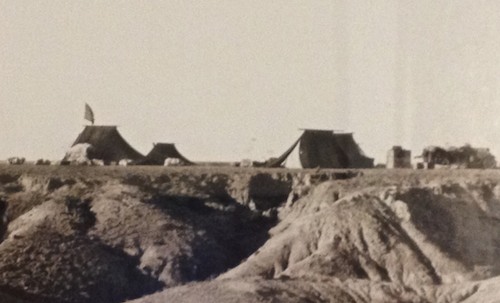

similar to the one we had left. The tents were pitched on a great promontory

which projected far out into the basin. Near them was an obo, or religious

monument, and shortly after our arrival two lamas came to call. They were

delegates from a temple, Tukhum-in-Sumu, four miles away, and asked us

to be particularly careful not to shoot or kill any birds or animals on the

bluff. It was a very sacred spot and the spirits would be angry if we took

life in the vicinity. Of course, I agreed to respect their wishes and gave orders

at once. But we had promised more than we could fulfill, as events proved.

discovered close to the tents. A few days later the temperature suddenly

dropped in the late afternoon and the camp had a busy night. The tents

were invaded by an army of vipers which sought warmth and shelter. Lovell

was lying in bed when he saw a wriggling form cross the triangular patch of

moonlight in his tent door. He was about to get up to kill the snake when

he decided to have a look about before he put his bare feet upon the ground.

Reaching for his electric flashlamp, he leaned out of bed and discovered a

viper coiled about each of the legs of his camp cot. A collector’s pickax was

within reach and with it Lovell disposed of the two snakes which had hoped

to share his bed. Then he began a still-hunt for the viper that had first

crossed the patch of moonlight in the door and which he knew was some-

where in the tent. He was hardly out of bed when an enormous serpent

crawled out from under a gasoline box near the head of his cot. Lovell was having rather a lively evening of it — but he was not alone.

found a snake coiled up in his shoe. Having killed it, he picked up his soft

cap which was lying on the ground and a viper fell out of that. Doctor Loucks

actually put his hand on one which was lying on a pile of shotgun cases. We

named the place “Viper Camp,” because forty-seven snakes were killed in

the tents. Fortunately, the cold had made them sluggish and they did not

strike quickly. Wolf, the police dog, was the only one of our party to be

bitten. He was struck in the leg by a very small snake, but since George

Olsen treated the wound at once, he did not die. The poor animal was very

ill and suffered great pain, but recovered in thirty-six hours.

jumpy. The Chinese and Mongols deserted their tents, sleeping in the cars

and on camel boxes. The rest of us never moved after dark without a flash-

light in one hand and a pickax in the other. When I walked out of the tent

one evening, I stepped upon something soft and round. My yell brought

the whole camp out, only to find that the snake was a coil of rope ! We had

to break my promise to the lamas and kill the vipers, but our Mongols

remained firm. It was amusing to see one of them shooing a snake out of his

tent with a piece of cloth to a place where the Chinese could kill it. The

vipers were about the size of our copperheads, or perhaps a little larger.

While their fangs probably do not carry enough poison to kill a healthy man,

it would make him very ill.

we were camped. Their great number at this particular spot was due to the

fact that it was a sacred place and the Mongols would not kill them there.

This viper appears to be the only poisonous snake in the Gobi, and we

collected but one non-poisonous species. The climate is too dry and cold to

favor reptilian life.”