Obviously, drawing skills are fundamental for the creation of visual art, whether it’s representational or not. By “drawing” I mean having the hand/eye motor coordination to make the marks you want, where you want them and the way you want them with your tool of choice, whether or not you approach your work using lines or shapes.

For the purposes of this post, however, I am talking about the use of “dry media”- pencils, charcoal and the like on supports such as paper and canvas. Plus the ability to represent an animal realistically and accurately. It goes hand-in-hand with the development of what I’ll call “visual judgment”, which is how you learn when you’ve made a mistake and what you have to do to fix it.

Part of the inspiration for the following comes from a comment thread I recently saw on Facebook in which an artist flatly stated that “passion” was the most important component of a painting. I would submit that passion uninformed by technical skill in areas such as drawing, design, form, structure, light, value, color and the handling of edges creates work that might have a certain initial level of visual excitement, but won’t stand the test of time or even close scrutiny. To my mind, lack of skill creates visual distractions that get in the way of the artist’s ability to express their passion. I also think that it can be used as a convenient excuse to get out of the hard work (it is HARD and it is WORK) of creating art.

I recently was a member of the jury which evaluated applications for membership in the Society of Animal Artists. Five votes were required for acceptance. The jurors were all artists with very keen eyes who were also uncompromising in their standards. I enjoyed the experience very much, both for the chance to see a lot of animal art and to learn from the other jurors. It was an objective process. The judging was not based on “like” vs. “not like” or “passion” or other vague emotional responses. The drawing of the animal was the first thing we looked at, whether it was a painting or a sculpture. Accuracy and an understanding of the structure of a species, plus a firm grasp of basic anatomy (“A leg can’t bend that way.”) were key. If the drawing of the animal was faulty, the application was rejected. It was one of the most consistent problems I saw in the work we viewed.

If, after taking a long, objective look at your work, you can see that there is room for improvement in your drawing skills, consider these books, which are from my own library and that I have found useful over the years. In no particular order:

-Drawing and Painting Animals by Edward Aldrich

-Animal Drawing, Anatomy and Action for Artists by Charles R. Knight

-Animal Drawing and Painting by Walter J. Wilwerding

-The Art of Animal Drawing by Ken Hultgren

-Drawing Animals by Victor Ambrus

-The Animal Art of Bob Kuhn…A Lifetime of Drawing and Painting by Bob Kuhn

-Drawing With An Open Mind by Ted Seth Jacobs

-The Pencil by Paul Calle

-Fast Sketching Techniques by David Rankin

And, for animal anatomy, you need both of these:

An Atlas of Animal Anatomy for Artists by W. Ellenberger, H. Dittrich and H. Baum

Animal Anatomy for Artists, The Elements of Form by Eliot Goldfinger

I’m sure that there are other good and useful books about animal drawing and anatomy and I invite you to share them via the comments section.

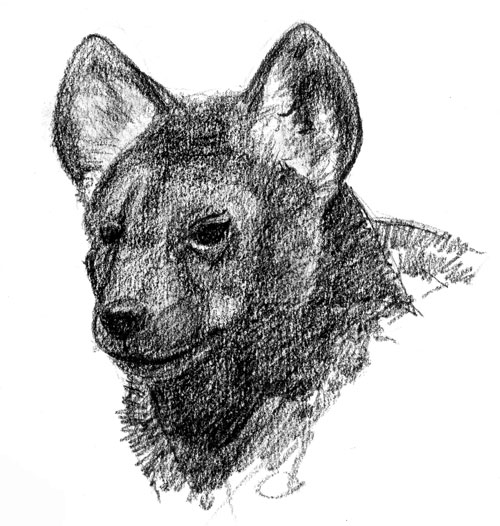

I’ve personally found the 3/4 view difficult, at least partly because I know that the camera flattens and distorts the form. This is a case where I draw what I know rather than what I see in the image.

I’ve personally found the 3/4 view difficult, at least partly because I know that the camera flattens and distorts the form. This is a case where I draw what I know rather than what I see in the image.

Profile is good, also. Then you can see how the nose fits into the rest of the head without worrying about perspective. Pick what you want to emphasize and downplay the rest.

Profile is good, also. Then you can see how the nose fits into the rest of the head without worrying about perspective. Pick what you want to emphasize and downplay the rest. Bird’s beaks are really hard to see close up in the field, generally because they’re small and the owners don’t tend to hold still for long. A captive bird may be your best bet because you don’t want to get caught faking it. But beware captive raptors whose beak tips won’t show the wear that the wild ones will.

Bird’s beaks are really hard to see close up in the field, generally because they’re small and the owners don’t tend to hold still for long. A captive bird may be your best bet because you don’t want to get caught faking it. But beware captive raptors whose beak tips won’t show the wear that the wild ones will. Cat noses are fairly similar in form. Variations on a theme, more or less. So drawing your house cat’s nose can be good practice for the big, wild guys.

Cat noses are fairly similar in form. Variations on a theme, more or less. So drawing your house cat’s nose can be good practice for the big, wild guys. It’s always great to get good reference of unusual angles, like this one looking up. It helps to see how the lower jaw fits with the upper jaw. Note how I have created a sense of three dimensional form by “wrapping” the right hand upper lip around the lower jaw.

It’s always great to get good reference of unusual angles, like this one looking up. It helps to see how the lower jaw fits with the upper jaw. Note how I have created a sense of three dimensional form by “wrapping” the right hand upper lip around the lower jaw.